The Byrds were an American rock band. As pioneers of folk and country rock, they are among the most influential music groups of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Band history

Beginnings

In the early 1960s, some young folk and bluegrass musicians came together in Los Angeles. Roger McGuinn, originally from Chicago (born July 13, 1942, as James Joseph McGuinn III, briefly: Jim McGuinn), had already collaborated with numerous bands and musicians and mastered several instruments. Originally emerging from the folk movement, he was particularly influenced by the Beatles. He changed his first name to Roger in 1967 after an Indian guru advised him to do so.

Born in rural Tipton, Missouri, Gene Clark (* November 17, 1944, as Harold Eugene Clark, † 1991) was passionate about country and bluegrass music in his childhood, but then switched to folk music. He was an experienced songwriter, who sold his first song at the age of fourteen. In 1963, he joined the New Christy Minstrels, who were at the height of their popularity during those years. In early 1964, he moved to Los Angeles, where he met McGuinn in a club. The two discovered their shared love for the Beatles and decided to perform as a duo from then on.

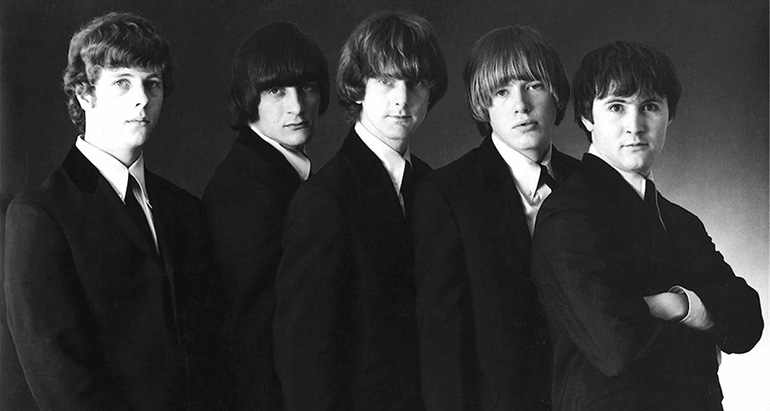

In the same club, the Los Angeles-born David Crosby (* August 14, 1941, as David van Cortlandt Crosby) occasionally performed. Crosby was a spoiled, rebellious son of wealthy parents. He was expelled from several schools and got into trouble with the law early on. Folk music finally offered him the opportunity to realize himself. Crosby, Clark, and McGuinn hit it off immediately. The producer and manager Jim Dickson, who had recently founded Tickson Music with his partner Eddie Tickner and 200 dollars, offered his help to the trio. Dickson had the advantage of having access to the Hollywood World-Pacific recording studio, which belonged to a friend, at nite. This way, his protégés, who called themselves the “Jet Set,” could rehearse and record demo tapes without interruption.

The drummer Michael Clarke (* June 3, 1946 as Michael James Dick, † 1993) was hired. Jim Dickson finally persuaded Chris Hillman (* December 4, 1944), a young mandolin player, to join the “Jet Set” as a bassist. The bluegrass musician Hillman had already made a name for himself as a member of the Golden State Boys (later renamed “The Hillmen”), where he had played country music with the brother duo Rex and Vern Gosdin.

In October 1964, the single “Please Let Me Love You” was released on the independent Elektra label, but it remained largely unnoticed. To give the band a British touch, the label changed the group’s name to “Beefeaters.”

1964–1966 First successes with folk rock

In lengthy studio sessions, the band gradually developed a distinctive sound characterized by Roger McGuinn’s twelve-string Rickenbacker 360 guitar and three-part harmony vocals. Gene Clark wrote most of the songs, partly together with McGuinn. One day, Jim Dickson suggested recording Bob Dylan’s song “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The three leaders McGuinn, Clark and Crosby were decidedly against it. Only when Bob Dylan personally showed up in the studio and expressed his interest in the new band did the musicians change their minds.

In the nearby clubs, the band had their first performances. The record label Columbia Records took notice of the up-and-coming musicians and signed them in November 1964, initially including only McGuinn, Clark, and Crosby. Hillman and Clarke followed six months later. First, a new name was sought. They decided on Birds (English for birds or also young girls). To avoid ambiguities, the “i” was replaced with a “y” (in reference to the “y” in Bob Dylan).

Under the guidance of the young producer Terry Melcher, son of actress and singer Doris Day, Mr. Tambourine Man was recorded on January 20, 1965. Chris Hillman and Michael Clarke were replaced by session musicians from the Wrecking Crew. The Gene Clark composition “I Knew I’d Want You” was chosen as the B-side. The conservative CBS management hesitated to release the single; it was only when Bob Dylan intervened again that they changed their minds. On April 12, Mr. Tambourine Man was released. After a few weeks, the song reached number one on the Billboard charts. An engagement as the opening act for the Rolling Stones further contributed to their popularity.

On June 21, 1965, the debut album Mr. Tambourine Man and the next single, the Dylan composition All I Really Want to Do, were released. The song reached number 40 on the Billboard Top 100. In August, the Byrds traveled to England immediately after a grueling U.S. tour, where they were announced as “America’s answer to the Beatles.” Their press officer at the time was Derek Taylor, who had previously worked for the Beatles. Practically without breaks, concerts, club appearances, press conferences, and television shows followed one after the other. The musicians, who were struggling with health problems and inadequate equipment, were often met with a hostile audience. The press also reported mostly negatively.

The Byrds’ third single, the Pete Seeger song “Turn! Turn! Turn!”, which had previously been interpreted by Judy Collins, was released after long and arduous recording sessions in early October 1965 and reached number one on the Billboard charts. Under considerable time pressure from the record company, which did not want to miss the Christmas business, an album of the same name was subsequently completed. There were frequent arguments in the band, which sometimes turned into physical fights. The trigger was usually the egocentric David Crosby, who felt sidelined by the musical leaders Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark. Power struggles within the group eventually led to the ousting of successful producer Terry Melcher, who had never managed to forge a real relationship with the individual musicians (with the exception of McGuinn).

The Byrds increasingly distanced themselves from their folk roots and their mentor Bob Dylan. The Beatles, John Coltrane, and above all the Indian Ravi Shankar became new musical role models. The sitar was adapted by McGuinn’s twelve-string Rickenbacker. On March 14, 1966, the single “Eight Miles High,” written by Gene Clark, was released. The title was about a flight from Los Angeles to London (“eight miles high”), but was understood by many as a euphemism for an LSD trip (LSD is one of the strongest known hallucinogens). The psychedelic-sounding music did the rest: numerous radio stations boycotted the song. The single reached number 14.

1966–1967 The Byrds without Gene Clark

In March 1966, Gene Clark left the Byrds. Main reasons were fear of flying and tour stress. However, he often felt that he was not sufficiently recognized by the other group members, who envied him for his success as a songwriter (and the associated royalties). Crosby’s aggressions, which often targeted the unstable Clark, also likely played a role.

Meanwhile, groups like The Lovin’ Spoonful, Simon & Garfunkel, and The Mamas and the Papas had emerged as competitors, encroaching on the folk-rock territory that the Byrds had musically explored. Their next single, the McGuinn song “Fifth Dimension,” only reached a middle position on the Billboard Hot 100. An album of the same name was then completed with great difficulty, and musically it was a significant drop from its two predecessors. There was a threat of a decline or even a complete breakup of the quartet.

In this situation, the musicians and management came together once more and focused on the production of the next album, Younger Than Yesterday, which was recorded in just eleven days at the end of 1966. It contained the song So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star, which had been released as a single shortly before, with which the Byrds commented on the Monkees’ origin story in a sarcastic and ironic way. Additional tracks were contributed by Chris Hillman, who made his debut as a songwriter. The guitarist Clarence White, who contributed to two songs, also made his debut with the Byrds here. After Clark’s departure, Crosby had increasingly taken center stage and competed with McGuinn for musical dominance in the group. He repeatedly stated that prominent musicians (such as Stephen Stills) were interested in collaborating with him.

Despite all the internal problems, the band achieved a triumphant performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in June 1967. However, the rebellious Crosby, without consulting the others, took to the stage with Buffalo Springfield, thus initiating his exit from the band. The following weeks were marked by disputes and jealousy. At Crosby’s behest, manager Jim Dickson was replaced by Larry Spector. In October, McGuinn and Hillman informed Crosby that he was no longer welcome in the Byrds.

For a short time, the Byrds continued their career as a trio. A return of Gene Clark failed due to his mental health issues. At the end of 1967, they parted ways with drummer Michael Clarke. The Byrds consisted only of Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman.

1968 Gram Parsons and Country Music

As early as January 1968, a new drummer, Kevin Kelley, was hired. Kelley was a cousin of Hillman and had already worked with Ry Cooder. Shortly thereafter, the album The Notorious Byrd Brothers was released, which had previously been recorded by McGuinn, Hillman, Clarke (and on some songs, Crosby) and studio musicians.

Another musician was sought, a jazz pianist at McGuinn’s request. Thru Hillman’s mediation, the highly talented multi-instrumentalist Gram Parsons (* November 5, 1946, in Winter Haven, Florida, † 1973) was engaged in early 1968, who had previously played with the International Submarine Band. McGuinn was only inadequately informed about Parsons’ past as a country musician. He soon managed to win over the bluegrass enthusiast Hillman. Together, they convinced McGuinn to try merging country music and rock. McGuinn was fundamentally ready to enter new musical territory and postponed his jazz plans to a later date. Gram Parsons, who quickly dominated the Byrds musically, pushed for a move to Nashville, the ultra-conservative center of country music. With noticeably shorter hair, they even had an appearance at the Grand Ole Opry. In the local CBS studio, with the support of renowned session musicians from the country scene, the album “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” was recorded. No established band had ever made such a radical stylistic change. The album featured classic country instruments such as the fiddle and steel guitar. Some songs had religious content. The Byrds were once again a step ahead of everyone else. Dylan’s Nashville Skyline would follow later. But despite mostly good reviews, the album didn’t sell very well.

For the public, McGuinn remained the undisputed frontman, but musically, Gram Parsons had gained the upper hand. He continued to make every effort to keep the Byrds on a country course. An attempt to establish steel guitarist Jay Dee Maness (and shortly thereafter Sneaky Pete Kleinow) as an official member of the Byrds failed due to McGuinn’s resistance.

In July 1968, a tour thru South Africa was on the agenda. The nite before the flight to Johannesburg, Gram Parsons jumped ship. The move was prompted by a comment from his idol Keith Richards, “you don’t go to South Africa.” Chris Hillman had a tantrum, while Roger McGuinn was relieved to be rid of the domineering Parsons. The tour was a disaster. The Byrds’ notoriously weak live performance was dramatically worsened by the loss of their musical genius. Fortunately, they encountered a grateful and undemanding audience, so the negative consequences were limited.

1968–1969 The Byrds without Chris Hillman

As early as August 1968, the bluegrass musician Clarence White (1944–1973, born in Lewiston, Maine) was found to be a worthy successor to Gram Parsons. White had previously been a member of the Kentucky Colonels and had founded the group Nashville West in 1966. Here, the drummer Gene Parsons (* September 4, 1944 in Los Angeles, not related to Gram Parsons) was also a member, replacing Kevin Kelley.

Almost simultaneously with Gene Parsons’ engagement, Chris Hillman gave up. Having been unhappy with the chaotic conditions within the band for some time, a dispute with manager Larry Spector was the final trigger. The founding member of the Byrds withdrew bitterly, only to resurrect the Flying Burrito Brothers together with Gram Parsons and Sneaky Pete Kleinow. As a replacement, John York (* August 3, 1946 in White Plains, New York) was hired, who had previously worked with Clarence White.

The constant changes in personnel and style inevitably had a negative impact on the band’s public image. After the disappointing sales of the last album, they even got into financial difficulties. Nevertheless, they managed to record an acceptable album with Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde, which was again country rock-oriented and contained Drugstore Truck Drivin’ Man, a piece that McGuinn had written with Gram Parsons. It was also the only Byrds album on which McGuinn sang all the lead vocals.

1969–1973 Successes as a live band

While the Byrds struggled to survive, David Crosby celebrated a triumphant debut at the Woodstock Festival with his new companions Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, and Neil Young. McGuinn, on the other hand, was still unhappy with his band. In September, he replaced the bassist John York with Skip Battin. In November, the album Ballad of Easy Rider was released, which tried to ride the trend triggered by the film Easy Rider, but in reality was a mix of different styles. Only three songs were written by band members themselves.

After a successful European tour in the summer of 1970, the Byrds began working on their next album, Untitled, which consisted of a studio and a live LP. It was almost able to reach the level of the first albums again. The success of Crosby, who had now risen to superstar status, had once again ignited the group’s ambition. The new work was commercially very successful (including the single “Chestnut Mare”). The idea of producing a mixed double album had brought the Byrds back into the public eye. In 1971, the Byrds were finally able to shed their once miserable reputation as a live band during their successful tour of England. In the middle of the year, the album Byrdmaniax was released, which caused controversy due to its questionable quality. The Byrds accused producer Terry Melcher of ruining the songs by arbitrarily adding background vocals and string arrangements. He justified his actions by claiming that he had upgraded a musically second-rate album.

In response to Byrdmaniax, the album Farther Along was recorded just a few months later. To avoid interference from the record company, it was produced in a London studio. The disputes within the group continued to increase. In July, McGuinn fired drummer Gene Parsons. He had often complained about the unfair distribution of money, but at the same time revealed significant musical weaknesses. John Guerin was used for recording sessions and concerts for several months. Bassist Skip Battin was let go in May 1972. The band then consisted only of Roger McGuinn and Clarence White. In early 1973, both decided to go their separate ways. The Byrds had ceased to exist.

1973 Brief Reunion with Original Lineup

In parallel with the activities of the Byrds, Roger McGuinn had been working for some time on the preparations for the production of a reunion album with the original members. His dream was to get together annually in the future to record a joint album and give some concerts. The record companies were cooperative. The financial success was almost guaranteed. The first joint album, Byrds, was released in April 1973 on the Asylum label, where David Crosby was under contract. Almost every band member had contributed songs. The public’s reaction was not very positive. People had expected more from the stars. Even the Byrds themselves were critical of their own work. They admitted that they had not spent enough time recording the songs and had thus achieved only a mediocre result. The disappointment was so great that plans for a major tour of the USA and North America were abandoned.

McGuinn, the holder of the name rights, had no interest in reviving the Byrds. Instead, he produced an ambitious solo album, which, despite the involvement of Bob Dylan, sold very poorly. In July 1973, a tragic accident occurred. Clarence White, who had been the most important musical contributor alongside McGuinn in recent years, was run over and fatally injured by a drunk driver after a concert. A few months later, Gram Parsons died of a drug and alcohol overdose.

1977 Second Reunion (as McGuinn, Clark & Hillman)

In September 1977, Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark decided to work together as a duo. At the end of the year, Chris Hillman joined. They no longer wanted to use the name Byrds because McGuinn only considered it appropriate for the original full lineup, and McGuinn, Clark, and Hillman believed that with their new music, they could appeal to both old and new fans. After some international tours, their first joint album, McGuinn, Clark & Hillman, was released in February 1979. It had little in common with the Byrds’ sound and was received quite positively by the audience. It even contained a minor hit with “Don’t You Write Her Off.” After producing the second album, City, Clark left, and McGuinn and Hillman continued to work as a duo for a short time. They released the largely ignored album McGuinn-Hillman.

1990 Third Reunion (McGuinn, Crosby, Hillman)

In 1990, Roger McGuinn, David Crosby, and Chris Hillman came together for a brief Byrds reunion, which resulted in four new studio recordings and a spectacular and documented concert as part of the Roy Orbison Tribute. Bob Dylan also performed at the concert, as he had in 1965. The aim of this project was to prevent the two remaining founding members, Gene Clark and Michael Clarke, from continuing to tour as “The Byrds.” However, a subsequent lawsuit by McGuinn, Crosby, and Hillman was lost. Gene Clark did not use the name until his death in 1991, but Michael Clarke did, until his death in 1992, along with Skip Battin and others. In 1991, on the occasion of their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, all five original Byrds met on stage for the last time.

Significance

In the year the band was founded in 1964, the Byrds’ musical background reflected the musical world of white people in the USA. Roger McGuinn had worked with folk trios, Judy Collins, and also Bobby Darin, who was one of the prominent rock ‘n’ roll stars in the 1950s and later turned to jazz. Gene Clark had been a member of the New Christy Minstrels, a typical American youth choir that became more popular with modern arrangements of folk songs. David Crosby had been persuaded by his brother Ethan to abandon jazz and combine his early solo repertoire with folk and blues. Chris Hillman had been a mandolinist in bluegrass formations.

These styles did not correspond to the general musical taste, but rather to the need of many young people to distance themselves from the superficial popular music. In the context of social and political processes in society, a kind of “bohemia” was founded with centers like Greenwich Village, where artists of all kinds exchanged ideas. The “Beatlemania” was initially rejected by these circles as commercial and unpretentious, but it ultimately had a highly attractive effect on young musicians, leading to the adaptation of elements of beat music (Merseybeat) to folk, blues, jazz, and country. In the case of the Byrds, this primarily involved American folk, especially in the style of popular folk musicians like Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, and others.

The Byrds were also inspired by the Beatles’ tendency from 1965 to not serve the audience with old familiar things, but to go new ways. Gene Clark’s song Eight Miles High was linked to the jazz of John Coltrane, the poem Kız Çocuğu by Turkish poet Nazım Hikmet was set to music by McGuinn as I Come and Stand at Every Door, David Crosby made bold steps toward jazz and psychedelic, while Chris Hillman opened new paths in country music with his compositions.

The circle was closed in 1968 when the band was convinced by Gram Parsons’ “mission” to record an almost pure country album with Sweetheart of the Rodeo. The Byrds have since been regarded as the founders of the musical styles folk rock and country rock. The elements of their music (folk, country, jazz, and rock adaptations with sophisticated choral arrangements and the typical Rickenbacker guitar) continue to inspire many artists to this day. But especially their courage to explore new musical paths and not to submit to the programs of record companies underpins the high significance of this formation.

Rolling Stone ranked the Byrds 45th on its list of the 100 greatest musicians of all time.